“New Mexico was the greatest experience from the outside world that I have ever had. The moment I saw the brilliant, proud morning shine high up over the deserts of Santa Fe, something stood still in my soul, and I started to attend. In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly, and the old world gave way to a new.”

DH Lawrence, an Englishman, wrote that in the late 1920s. He was suffering from the bouts of tuberculosis which would eventually take his life and had travelled to the American south-west in search of clean air, altitude and freedom from the censors of Europe.

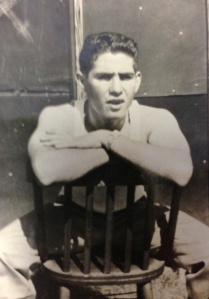

Not so many years later, my uncle, Amir Espat, whose lineage ran from Lebanon to Guatemala to Belize, travelled up to the United States and made his way to New Mexico.

Like Lawrence, he was taken with the light. New Mexico has very big skies. They are not like the skies of England, the skies of a man content to describe what’s in front of him. They are vast. They are skies for dreamers.

He arrived with little to his name. But over the decades that followed he would build a life there. And he would paint, endlessly, using the dusty, quixotic colours of New Mexico.

A few months ago, just after his funeral, I stood in my uncle’s studio. His glasses – dreadful, oversized beige frames from the 1970’s – were still on the desk. His paint was still smudged together in new exploratory mixtures on the pallet, a last unfinished work still on the stand. There was the latest copy of Time magazine, carrying a front-page report on Syria, which he would never read.

We are not in the things we leave behind. Even the objects we associate with our loved ones feel empty and stale once they are gone. They are just artefacts; debris of life. These objects did not love him. The sheets he slept in did not love him, nor did his favourite chair. Even the paintings he made did not love him.

Without him, they are relics.

Marx said that you could define humankind by its ability to adapt the world around it. Our ‘species essence’ lay in our desire and ability to remould the world, to labour upon it. Man built bridges and sewage systems, mined oceans and designed cities. And man also devised poetry and politics. Man arranged his habitat around his life rather than the other way round. He impacted on the world.

My uncle was a short man, but under Marx’s conception he was very big. He moulded the world to how he wanted it.

He went to New Mexico and he built a life. In the end, it turned out he was the advance party for a family which would set down roots: my family, a very big and difficult and generous family.

He built a business, with a mind that was no less entrepreneurial simply because it was also artistic. He became wealthy. He designed and built homes. He was a very accomplished architect, carrying with him that great American preoccupation with space and air.

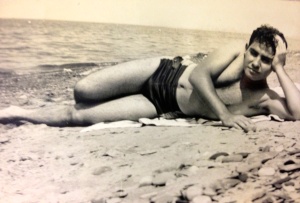

He stamped his homes with his personality. He carved statues onto the rocks in the garden of his house in Albuquerque. One of them is of his wife lounging in the sun, a testament to his timeless fixation with her beauty.

At the front of the house, visible to anyone driving by, stands a statue of a tall couple gazing out to the horizon. They look old, haggard and distinctly indigenous. But more than anything they look proud. They are a tribute to his abiding sympathies: with the immigrant, the outsider, the labourer. With he who aspires.

Inside the house, his paintings would fill every wall. He produced so many that other family members would take them for their own homes and eventually they became so ubiquitous they turned into totems. You would find them whenever you were in a house of the family. They are there now: in houses in Guatemala, Belize, America and Britain. But they are not just expressions of family. They are tiny Amir Espat machines. They leave impressions. They mould people.

They are hallucinatory and unreal. Glances of beautiful – almost supernatural – women melt into solitary visions of old men closing back doors, paramilitary thugs with guns, stricken widows gazing up at the sky, couples dancing in the night time.

They formed part of my childhood subconscious – a malleable place, like cooling wax, where early ideas are formed. They were immersive, restless and exotic. They attracted and they confounded.

His paintings were like him: open.

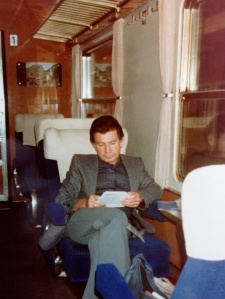

He was a man of the left, but also a man who had found wealth. He was an American patriot. No matter how furious he became with the rightward drift of the country, he never lost faith in the American ideal. He was a rationalist and a humanist. He despised religion.

His politics were not ideological. They were a way of looking at things: an enthusiasm for knowledge, a reflex towards compassion. They were an instinct, more than a destination.

A few years ago, his sister – my grandmother – died. It left him the last-but-one of a generation of eight – the first generation of the family to grow up in Central America.

I had been with my grandmother when she died and it had a severe effect on me. The world felt fragile and unreliable.

Once the well wishers had left the house, he started digging around in his sister’s ashes. My mother and I were horrified, but he had this childlike smile on his face. “It’s not really ashes,” he said. “They just call it that to make people feel better. It’s really tiny bits of bone.” He held one piece between his fingers and showed it to me. “See?”

He knew she was not there.

He was profoundly unsentimental. For a man with a warm smile he was never misty eyed. He did not give much thought to niceties or expectation.

But he had dragged that which was unspeakable into the daylight. He took something which was big and scary and heartbreaking and approached it with childlike curiosity. He recognised that love did not need to be protected by superstition and taboo.

Being unsentimental isn’t about limiting your feelings. It’s about not going through the motions. It is ultimately about being true to your feelings.

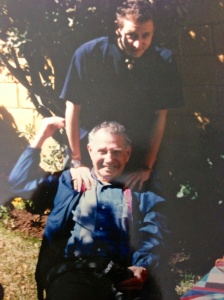

He was always smiling when he saw me. He used to hold me firmly at arms’ length, look me up and down, nod and then embrace me. But he always took a look at me first. It was never by custom. It was never theatrical. It was always genuine, always considered.

The smile he gave me was one of those big smiles you get from people who are genuinely pleased to see you. Consciously or subconsciously, we can all tell the difference. We know how eyes look when they find themselves gazing upon something they truly value. Now there is one less person in the world who looks at me like that. And I have one less person to look at that way.

He loved England, probably as the result of a Belizean education. No-one could say a bad word about the place. He thought of it as somewhere that was civilised and humane. I always wanted it to live up to his expectations.

The last time he visited – a few months back – we spent a summer afternoon drinking and eating in Hyde Park. People were talking but he had stopped listening. He was lying on his back, perhaps a little tipsy, staring up at the leaves in the tree above him.

“Have you ever written about trees?” he asked.

I’ve never written about trees. I find them comforting in the daytime and ominous in the night time. That is all I’ve ever thought about trees. But I realised that even in his mid-eighties he could still see the beauty in simple things. He knew how things were put together, but that did not stop him from experiencing wonder.

‘I must write about trees,’ I thought. ‘I must write about trees so he can read it.’

We are all engaged in a conspiracy against the dead. We mourn them, we miss them, but in general we do not speak of them. Those closest to them – the mother, the wife, the daughter – cannot help but do so. But when they do, you can see the people around them tense up. Everyone wishes it would go away.

It is not their fault. It is easy to upset someone who is mourning. Attempts to cheer them up can seem flippant and disrespectful. Attempts to console them can seem cloying and insincere. One is never sure when the bereaved wants to talk about it and when they would rather distract themselves. There is a lot of anger in those who mourn and it can quite easily be directed at whoever happens to be nearby.

But we don’t just tense up because of our fear of social upset. We tense up because we are being confronted with something which we pretend is not true: That life ends. That death is.

Many people berate Western culture for refusing to look death in the face. I am not sure I agree. After all, what is there to see? The abyss. Nothing more. There is so little to say about death. It cannot be problem-solved or managed, it cannot be traded or bought off. It is not a subject. It is the un-subject, the opposite of things. It is ending.

Very little of us survives death. We do not remain in the objects we leave behind, or even in our arts or constructions. We do not remain in the money or the houses.

Dozens of my family members live in New Mexico because he arrived one day, like DH Lawrence, and admired the sky. But he does not live on in this fact any more than he would die again if someone leaves.

We do not even live on in memory. That which is past is past. It is not now. Memory is not living.

We live on only in one crucial aspect: in how far we have become a part of the living.

We live on if we embed ourself in the personalties of those we leave behind. In how we make them think or act.

We live on by moulding the world after we are gone.

Amir Espat was a short man, but he was very big.

He believed in the hand which reaches out to help rather than take for itself.

He believed in things that were bigger than money, better than money.

He believed in colour and materials, in giving people somewhere beautiful and dignified to live.

He believed in America and its better nature.

He believed in reason.

He believed in ideas and those confident enough to measure them.

He was as big and as vast as the skies of New Mexico.

That is such a beautifully expressed piece of writing. It shows just how deeply you carry him within. thanks Ian. Gail

What a man and what a profound and lyrical response to him, living so well, and truly.

What an absolutely beautiful piece of writing, Ian – about a very special man, but of course ultimately about how to treat death. Wow.

By far the best piece of writing by you.

You have me crying! What wonderful thoughts. We’ll cherish his memory always. Thanks. Tia

This is a beautiful testimonial, Ian, to a beautiful person whom we all miss so much. And it is beautifully written. Thank you—all of it resonates with the Amir we all loved so much. You have captured his essence very well.

So profound and beautiful…

I was very touched by your thoughts and impressions of Amir. Mum