Chileans are the only people I know of who have formalised the process of starting a romantic relationship. They call it ‘pedis polelelo’. It’s basically a proposal to become boyfriend and girlfriend. Of course, they’ve usually kissed or slept together by this point – they’re not freaks – but you’re not technically going out until this event has taken place. Like marriage proposals they can be either simple or elaborate. And like marriage proposals, it’s usually the man who does it.

One one level, this is pure genius. I’ve lost count of the conversations I’ve had with people who are unclear as to whether they’re going out yet. How many coffees or beers have we all had with friends as they ponder whether they’re technically in a relationship with the person they’re dating?

My usual advice takes the form of asking whether it’s OK for them to sleep with someone else. If the answer is no, they’re in a relationship. Sexual exclusivity is the best functioning definition of it. (Unless you’re in an open relationship blah blah blah. I find people in open relationships the most tedious people to talk to about this subject. They love telling you about the rules, they all have a tremor of emotional catastrophe going on just behind the eyes and none of them are half as interesting as they think they are.)

The proposal also clears up that old question pre-married couples love asking each other: Which day shall we pick as our anniversary? Our first kiss, our first shag or something else? Under this system, the day you pidiste polelelo is the official starting date. Job done.

It clears up many things and makes perfect sense. And it’s typical of the way Chileans seems intent on imposing order in the midst of total chaos.

Chileans love comparing themselves favourably to other Latinos, especially now that Argentina’s empty box economy is falling apart in plain sight. Their sense of nationhood seems partly to be defined by an (entirely valid) perception that they are a bastion of order in a continent of chaos. They proudly tell you they work like Europeans, by which they mean hard. Even the Germans are impressed. A German logistics officer told me admiringly that they are very good military shoppers. “They buy their warships from the British and their infantry equipment from the Germans,” he said with a wry smile. It’s all very well organised.

But amidst this order, the landscape is borderline uninhabitable. The northern part of Chile, which I’m passing through now, is gradually turning into desert. There are cacti everywhere. The ground is dry and majestic, with big sweeping mountains waving up on every horizon. A strange red plant – it looks like the kind of thing which would give someone super powers in a Marvel film – covers huge patches of earth. Every mile you go it becomes more and more like Tatooine. And it’ll only become more severe as I approach the Atacama desert, which Nasa uses to trail equipment for use on Mars. It’s as close to an alien landscape as you’ll find on earth.

Nearly all of it is empty. Almost ninety per cent of Chile’s population lives in the greater Santiago area, so there’s hardly anyone left to live here. The journeys between towns are severe affairs, taking days. After all, this is a sliver of continent masquerading as a country. It is just taking the piss with how long it is.

There are hardly any cars on the road or settlements. You look out the window for hours on end without seeing any signs of life, except for the occasional flapping white flags of sweet bun sellers, who board the coaches to sell their wares to the passengers.

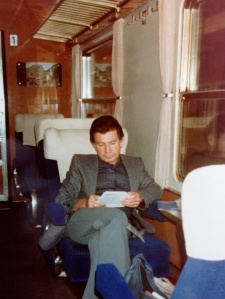

But even in this landscape, Chilean order endures. The sweet bun sellers are picked up in one location, then dropped off at the next, where they wait for a coach in the other direction to start the process again. Before I knew how this system operated I asked the conductor whether we would be stopping for food. He looked at me as if I were mad. Nothing is allowed to slow the progress of the vehicle.

The sleepy, dusty towns are full of polite, reserved workers. The buses ferrying us between them are extremely comfortable, even luxurious. They arrive on time, leave on the dot and never take longer than five minutes to disembark passengers, pick up new ones, and set off again. Once you’re aboard, a ticket operator comes on and checks your papers, including your passport or national ID number.

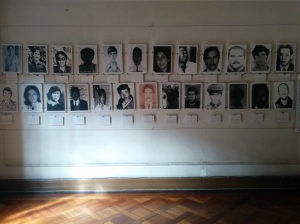

I obviously wasn’t very impressed by the demand for identification on a bus, but then it’s to this country’s great credit that you have to remind yourself how recently they were a military dictatorship. That Chilean sense of order isn’t just a defensive barricade against the landscape, or a bulwark against Latino poverty and chaos. It’s also an underlying current of fascism and fear of fascism.

Take the police, who summarise many of the tensions in Chilean society. On the one hand, they are the only police force I know of in Latin America who don’t take bribes. The people here, who almost all instinctively distrust them, are rightly very proud of this. Women also tell me they can be trusted and that they would seek help from them if they were attacked. Again, that wouldn’t necessarily be the case in many other Latin countries. In Guatemala, for instance, many of them are just heavily armed children – often given shotguns, with their spray of pellets, as a substitute for teaching them how to shoot.

But Chilean police are also brutal. They have a reputation for being incredibly violent during the frequent student demonstrations here.

A couple of days ago I saw two of them take down an aggressive drunk by the beach. At first, all I could see were flying fists, but then I spotted the signature brown uniform. I’ve seen police take people down brutally in England before. But even then their actions are clearly deliberate and trained – pressure points, or responses to orders, or specifics blows to the solar plexus to temporarily incapacitate someone. This was different. It was a brawl. Punches to the face, headlocks, a couple of kicks to the ribs: a pub fight.

Technically the police are called ‘carabineros’. But every Chilean I’ve met refers to them by the vaguely disparaging term ‘pacos’. I’m told there are efforts to make it illegal to call them that. It gives some indication of the undercurrents of authoritarianism which Chilean orderliness can contain.